Drinking from the well of ancestral memory

Ghost curtain

Imagine the world tree, the great and mighty tree found in so many mythologies.

Here I am climbing Yggdrasil, the world tree in Norse myth which speaks to my ancient branch of Norwegian and Swedish ancestry. For me, Yggdrasil is a yew tree, though some say it's an ash tree. Perhaps your tree is a mighty oak. Whatever the species, its roots are travelling far, far down into the deep earth, into the Underworld. Its thick trunk sprouts a myriad of branches stretching so high into the sky that you can’t see where the green canopy touches the clouds. This tree has thousands of leaves, speaking on the wind, the voices of our ancestors whispering to us across time. Through my own ancestral and mythological research and practice, I’ve come to realise that the mythic world tree also represents our ancestral tree, stretching back through millenia to the lands where we were first birthed.

We are at Samhain, that time of year where the veil thins between worlds. A time to remember our ancestors, invite them across our thresholds into the warmth of our hearths. The more we know our ancestors, the more the leaves flourish on the great branches of our tree. The more nourishment that we give our ancestral roots, the more our tree thrives through the honouring, the remembering, and the telling of our ancestor stories. In doing so, we are healing the ancestors that may come forward for forgiveness. We may discover difficult and traumatic stories of suffering and persecution. This will make us feel uncomfortable but the discomfort is part of the process. It can't be ignored, it requires attention. Although they may be long dead, many of our forebears are seeking release in spirit through our discovery of them in long forgotten corners of the land.

A question which is very current at this time, as many of us seek to reappraise our past and shine light on hidden or suppressed histories, is this:

How do we find that place of compassion deep in our soulful hearts to forgive our ancestors? For the mistakes that they made, the suffering they may have caused or endured, and for the wounds that they may have passed down to us through the generations?

If we pay attention to these stories that emerge through the familial soil where we dig, there are often gifts to be given. For example, I worked with my great grandfather, an alcoholic and at times violent 19thC Glaswegian horse dealer of Scottish Irish lineage, nicknamed Black Jack for his dark humour and even darker moods. He passed down trauma in my family, but by paying attention to his story, the bits that I knew passed down, piecing the jigsaw together through history research, and then stirring into the creative cauldron and journeying with him in a drum journey, I discovered that he was ready to be forgiven. By working with him in spirit, in return he gave me a great white horse, who revealed to me her secret name - Crioch - which is both Old Irish and Scottish gaelic for boundary.

It is no surprise that the horse in Irish myth represents sovereignty. Once forgiven or remembered, your ancestors are ready to stand at your side. They will join the ‘well’ of loving ancestors who already keep you close. They will have your back, supporting you, holding you with the strength of your ancestral tree.

Let the sap rise through its trunk, fed by the Waters of Life flowing from the Well of Urd, filled with memory, located deep within its roots, your roots. Fed by soil from the lands fertilised with their bones and their scattered ash.

Remember your ancestors, these Old Ones. Know that they have not forgotten you. The more of your ancestors that you can trace and discover, that you walk with in the places they once lived, loved, toiled and died; the places that they sang, danced, and cried, the more they can resource you in troubled times. Once you begin to remember the stories of the land that they walked on, they will begin to walk alongside you.

You can call on your ancestors in these times of trouble, those healed ancestors who step forward to assist. I have found that by tending to my ancestors over time (this is slow bucket spade work requiring much research and digging), so many of my grandmothers and grandfathers down the lines are with me. I feel and hold their love deep within the chalice of my heart and I give them my love in return. Sometimes, when I am overwhelmed by the weight of responsibility and restrictions wrought by the pandemic, I remember the waves of disease that they lived through.The fact that my ancestors survived through millenia for me to be birthed is testament to their strength. Some lost whole families to epidemics such as the tragedy of my five young cousins wiped out by cholera within a week on a farm in Cornwall in 1842, or my cousins lost to Spanish flu in the early 1900s, whose grave in Plymouth I still tend because my mother and grandmother tended to them. So many diseases that once killed millions are now treatable or curable. Our ancestors know this because they trod the path before us. When we are enveloped in the emerald canopy of their stories that this great tree holds, we can begin to truly see its beauty. The scars and gnarls of its bark reflect our own and its fat fruit is ripe for the picking.

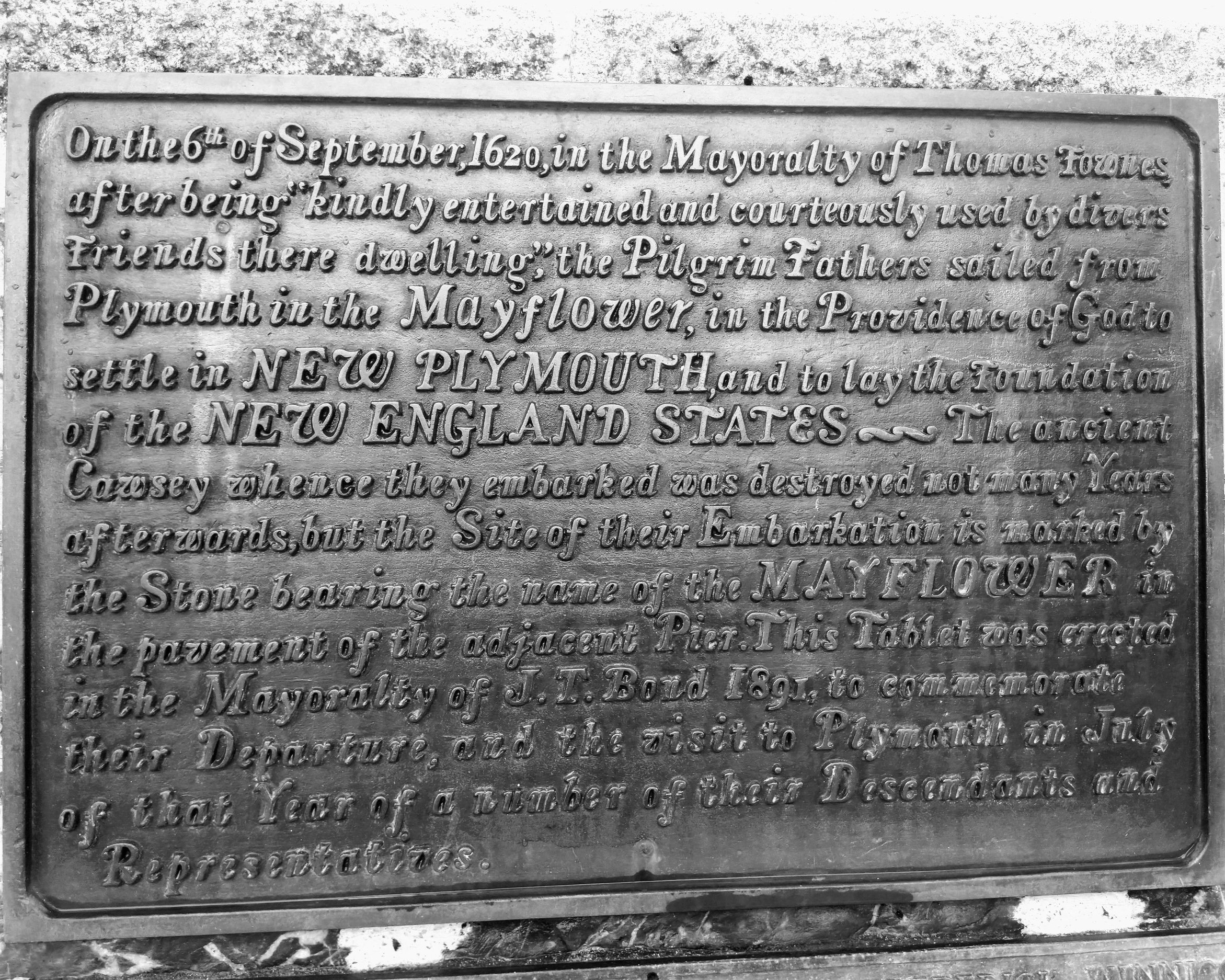

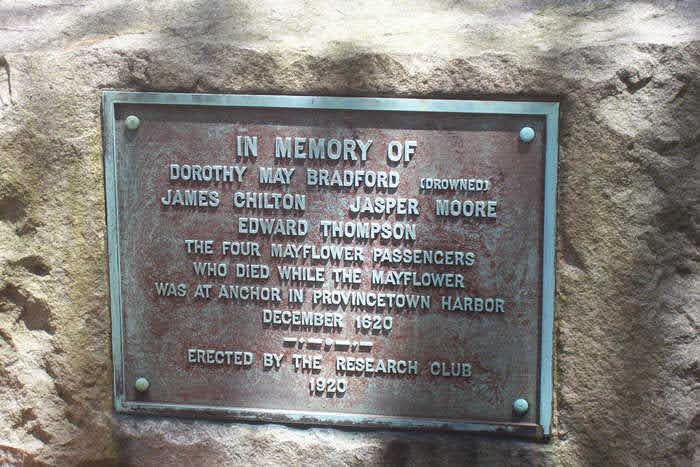

Come with me then, as I tell you a story of one of my ancestors whose story I worked with in 2020, which was also the 400th anniversary of the sailing of the Mayflower. It has required forgiveness, as it is a story of suffering and hardship, of people fleeing persecution, but who then brought disease, persecution and great suffering to the people on whose land they settled. My second cousins (thirteen generations ago) were William Bradford and his first wife Dorothy May Bradford. A young couple, religious Separatists who set sail on the Mayflower, departing Plymouth, Devon on 16 September 1620 to begin a new life thousands of miles across the Atlantic.

The women’s stories of this time are still so sketchy, as the history was written by their menfolk. After two months at sea, surviving the most horrendous conditions below deck, and two violent storms, the Mayflower anchored off Cape Cod. On 7 December 1620, whilst William was on shore scouting for land to settle, land which already belonged to the indigenous Wampanoag Pokanoket people, Dorothy, who was only 23, fell overboard into a flat calm freezing sea and drowned. Although there is no recorded detail of how or why she fell, I believe, as others do, she took her own life. Missing her young son left behind in the Netherlands, not knowing if she would ever see him again, exhausted by a terrible voyage, facing yet more uncertainty in unknown lands, and with disease already breaking out on the ship, I feel that she simply could not bear to go on.

I had been reading the account of the voyage and settlement Of Plymouth Plantation, written by her husband, William, in which Dorothy’s death was merely a one-line entry. Working with her story in a ceremonial way, fleshing out the detail of what might have been, I felt as though some weight had been lifted.

Dorothy May

Heavy bones

sodden with salt water

dragging wet foot

after wet foot

slowly towards the fire.

For four hundred years

you've lain as a post script,

a brief memory on a page,

no direct living lineage

to remember you

apart from your husband's descendents.

Do they sing for you now

Dorothy May?

First wife from Cambridgeshire

married at sweet sixteen

in Amsterdam, 1613

a move to Leiden,

back and forth,

back and forth,

birthing a baby,

beautiful boy,

you were just nineteen.

You had to leave him,

at three years too sickly to

step aboard the Speedwell,

then the Mayflower

into unknown horrors.

Tossed by the great storms at sea,

eight weeks crowded below deck

rolling in fever, puke, shit, and salt water

Was the escape to a new world

worth this?

You miss your son so deeply,

your husband scouting on new land

hung upside down from a tree,

caught in a deer trap,

will he return to the ship?

The dark waters are calling,

black obsidian mirror

reflecting tear streaked cheeks

as you lean over the deck

in the chill December air.

How can you make a life

in this strange land,

with so many hardships ahead?

You cry out for your son

as you fall head first into

the ice water,

the shock of the cold

with your thick wool

skirts a sponge

to weigh you down,

lungs filling quickly,

a crown of flowers

about your head,

hair streaming

in seaweed fronds.

The light goes out.

Was your body recovered floating

from Cape Cod,

were you buried ashore

in an unmarked grave

with those who died at anchor

from yet more fever?

You whisper that your bones are still

down there on the bed

in the soft silt sand.

Sodden, you soaked my copy

Of Plymouth Plantation on purpose,

the pages took time to dry,

you knew this release was coming

shedding tears on your husband's words

to be heard.

I remember you now,

Cousin Dorothy May,

with the ancestors who hold

you firm as you wet step

your way into the fire

flames as tall as grandmother trees,

William stood there behind you,

full of forgiveness

full of love

full of grief

full of regret

at what might have been.

It was about survival.

You can forgive him now,

your heart is as light

as a May flower.

After Dorothy died, William remarried a woman he had once courted back in England, Alice Carpenter.