A pilgrimage of the heart

You ripped my heart from my bones

and left me bleeding DNA

tears into the earth

for nearly 800 years.

Now, on this pilgrimage of the heart,

from Beaulieu to Tewkesbury,

by way of Hailes Abbey,

and back again, I have become lighter.

The drops of holy Christ blood long since

spilt; even saffron honey water can grant

forgiveness with the power of thought,

prayer, and footfall.

This once holiest of shrines

is now a grassy mound,

where bees collect nectar from clover

and camping couples sit reading,

not praying, on their nylon folding chairs,

in the late summer sun of Lugh.

Our son lies there still,

Henry of Almein,

in front of the high altar,

that most sacred of resting places,

where his bones bear the scars of the knife

beneath another tufted knoll.

His murderers are forgiven,

as I finally forgive you,

through hot tears shed under

the weeping willow

where moat water once sparkled

in summer sunlight.

Your grief for him was deep;

your conscience pricked

on your own death bed.

Oh King of the Romans,

high and mighty, you chose

the greatest beauties of our day

for your three wives. From elder to younger.

I, Isabel, your first bride, older, wiser,

you plucked me for my fertility,

for my form; though in my grief,

no man could ever be a full match

for Gilbert, my one true knight.

I was his virgin on my seventeenth birthday.

Already thirty seven, my rebel baron,

had sided with his father against yours,

to force the signing of the Magna Carta,

that great symbol of civil liberty.

Gilbert held my heart entwined

for thirteen years with our

six, strong, beautiful children

as testament.

All we knew was death, you and I.

The death of our sons,

the death of our daughter,

babes in my arms.

I screamed at the pain.

How I longed to be with Gilbert

as you whored your way round Europe

with your army of lovers.

Oh Holy Roman Emperor.

Nine years, two cot deaths;

a son’s murder - I forsaw it in the mirror;

my liver burst in anger with the birth of our last son.

The sum of our marriage.

You buried us together at Beaulieu,

because you could.

Because you, in your own sweet spite,

would not honour

my dying wish to return me to my first love,

whole and complete.

Your only concession was to cut out my heart,

in the spiritual fashion of the day,

locked in silver, lined with lead,

to send to Tewkesbury.

We’ve long since gone, Gilbert and I.

My heart and his bones scattered to the four winds.

I lay as forgotten as you,

whilst holy stones fell at our feet,

until a 19th century horse stuck its hoof in my grave,

tumbling.

Centuries later, an ancestor remembered.

She dreamed me, or perhaps I dreamed her.

That’s all it takes:

the passage of time,

one small act of remembrance,

one small act of forgiveness,

one small act of clarity and creativity

for me to forgive you,

to sing you a dragon song in a dusty church.

I am free, Richard; so now are you.

A song of joy rings out in Tewkesbury.

A pilgrimage of the heart coming home.

In 1240, a heart is placed in a silver-gilt heart casket by one of the most powerful, wealthiest men in Europe. Isabel Marshal, the wife of Richard, Earl of Cornwall, has just died in childbirth. He buries her and her son, against her dying wishes, in Beaulieu Abbey, founded by his father, King John of England. He sends her heart to be buried in Tewkesbury.

Nine years earlier, at age 21, Richard had married Isabel to the disapproval of his older brother, King Henry the third. Isabel was nine years his senior, a grieving widow of just five months, and already the mother of six children by the love of her life and first husband, Gilbert de Clare. Through their nine year marriage, Richard had many mistresses, while Isabel suffered the loss of their first two babies, a boy and a girl, both aged one, in consecutive years. Henry, their surviving third child, was later murdered in Italy by his cousins in 1271. His body was brought back and buried at Hailes Abbey, the place of his birth which Richard had founded fours years after surviving a near shipwreck and drowning during a violent storm at sea in 1242, and making a promise to his God in gratitude. Richard died in 1272 and was also buried at Hailes.

Was it a coincidence that he built his abbey just a few miles from Tewkesbury Abbey, whose great patrons were the family of Gilbert De Clare? Hailes Abbey grew to become one of the major pilgrimage destinations in Europe, especially after Richard’s son Edmund brought back a Holy Relic from Germany, a phial containing the supposed blood of Christ, which was enshrined at Hailes in 1270. Richard had been crowned King of the Romans in Germany, so it is likely that the phial had been in the possession of previous Holy Roman Emperors. Like so many medieval relics, it was later dismissed as a fake, but not before a great elaborate extension had been built to house the Holy Blood, and thousands of pilgrims had made their way to beg forgiveness and healing at its shrine. The phial even made its way into Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in the Pardoner's Tale. The 15th Century mystic, Margery Kempe, also visited the shrine where she wept loudly for forgiveness, making a great impression on the monks.

Hailes, along with Beaulieu Abbey, now lies a haunted ruin, the bones of its founders unmarked under grass. The spirit of Lady Joan Huddleston, one of the Abbey’s last great benefactors before the dissolution also lies buried there, making her presence known amongst the stone arches and in the English Heritage gift shop, throwing bottles and bags off the shelves, and upturning waste bin lids. The bin lid episode I saw with my very own eyes. There have been several sightings of her over the years, and I certainly had a great shiver run down my spine when I saw the photo which captured a woman’s shape clad in black Tudor style clothing, held in the museum shop. Lady Joan doesn’t feel malevolent, more a guardian of her spiritual investment.

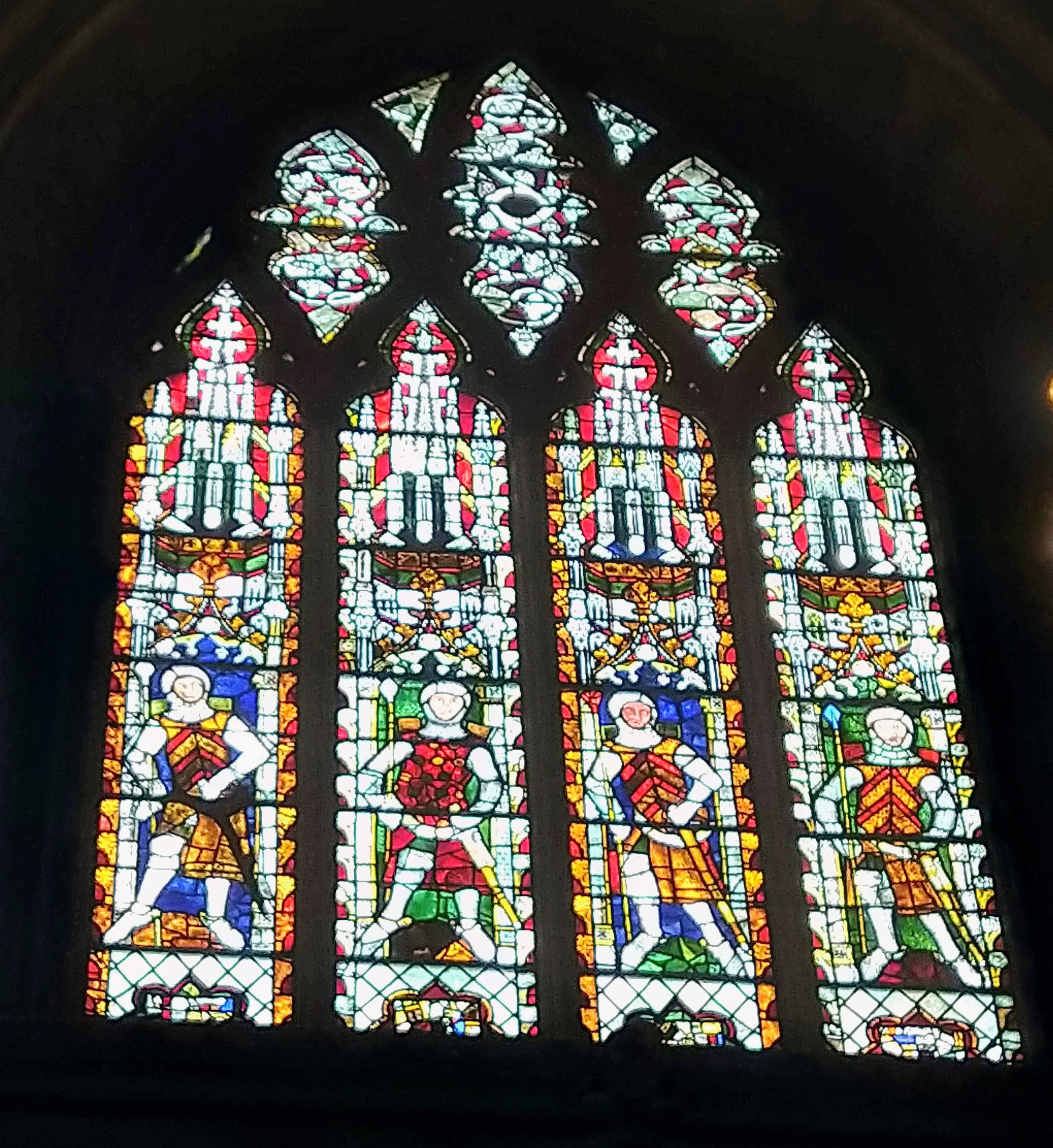

Tewkesbury on the other hand, still stands in all its glory, having survived the worst ravages of the dissolution. Gilbert looks own on his now empty tomb, marked with a brass plaque in front of the high altar, from his rare 14th Century stained glass window vantage point. From the first whispers of Isabel and her story in my ears in June 2019, asking me to connect her bones in the New Forest back to her heart, or at least its last known resting place, I had completed my own pilgrimage of the heart. Somehow Isabel feels at peace, finally burning off the residual vestiges of grief and anger after nearly 800 years when she found me. Or I her.

Why is it so many women are the ones left to forgive, mainly the actions of men, down through the centuries?

The art of forgiveness (though not forgetting) is the key to opening our hearts to unconditional love. In doing so, we free ourselves from many emotional burdens.

By doing so, we can help pave the way for the wounded warriors to ask for forgiveness, and in so doing forgive themselves.

My personal pilgrimage is not yet over. This stop on my ancestral trail of forgiveness is part of a bigger journey to the graveside of Isabel’s great grandfather, the Irish King of Leinster, who has a major historical burden buried in his casket which the poet and author W.B.Yeats wrote about in his play the Dreaming of the Bones.

Isabel Marshal, Countess of Cornwall, was born on 9 October 1200. She was my great grandmother, 23 times in the past through the twists and turns of my father’s line. Her daughter Isabel, fathered by Richard, died on 10 October 1234. I was born on 7 October 1968. My own son Vincent was stillborn on 2 May 2006. I sensed her anger and pain.

This is the pilgrimage of the heart.

The hardest path of all.

The runes and the roses are with me

every step of the way.